Having just returned from the grand tour of the Grand Canyon, I can say with authority that Edmund Burke didn’t know the half of it.

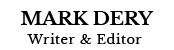

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818).

Burke never visited the vertiginous abyss that, more than any other natural wonder, embodies his belief that terror is the voltage from which the sublime draws its jolt. “The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature…is astonishment,” he wrote, in A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of The Sublime and Beautiful (1857). “And astonishment is that state of the soul in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror.”

To stand at the brink of the Grand Canyon is to thrill with dizzy horror at the mile-deep plunge mere inches away. Not for nothing is this bottomless pit called an “upside-down mountain”: Adjectives collapse. Exclamations go clunk. Attempts to wrap your intellect around the illimitable vastness of it all die stillborn in the brain. John Muir’s rhapsodic essay, “The Grand Canyon of the Colorado” (1902), soars highest, but even it falls dead to the floor when the reader sees the canyon with her own eyes. Nothing compares.

It’s an infinitely dense, endlessly collapsing hole in the psyche as well as the ground, this 277-mile long chasm, and you can almost feel its awful magnetism pulling you toward its edge, begging you to lean further…just a little further…that’s right…keep going…just another inch, over the spidery rails that keep you from plummeting into the infinity at your feet.

Trail sign, Grand Canyon National Park.

This is the sensation Poe nailed in “The Imp of the Perverse” (1850). A proto-Freudian meditation on the id (77 years before the father of the unconscious dreamed of that “dark, inaccessible part of our personality”), Poe’s philosophical fiction confronts the “radical, primitive, irreducible sentiment” that “has been…overlooked by all the moralists.” This sentiment insists on the cathartic release of the primal desires and infantile impulses suppressed by civilization. Irrational and “with certain minds, under certain conditions,” irresistible, Poe’s imp flouts drawing-room taboos, indulging itself in petty provocations that flirt with social suicide. At other times, when its fatal attraction to self-gratification overrides even the hardwired logic of self-preservation, the Imp of the Perverse risks self-destruction in the more literal sense:

We stand upon the brink of a precipice. We peer into the abyss—we grow sick and dizzy. Our first impulse is to shrink from the danger. Unaccountably we remain. By slow degrees our sickness and dizziness and horror become merged in a cloud of unnamable feeling. […] It is merely the idea of what would be our sensations during the sweeping precipitancy of a fall from such a height. And this fall—this rushing annihilation—for the very reason that it involves that one most ghastly and loathsome of all the most ghastly and loathsome images of death and suffering which have ever presented themselves to our imagination—for this very cause do we now the most vividly desire it. And because our reason violently deters us from the brink, therefore do we the most impetuously approach it. There is no passion in nature so demoniacally impatient, as that of him who, shuddering upon the edge of a precipice, thus meditates a Plunge. To indulge, for a moment, in any attempt at thought, is to be inevitably lost; for reflection but urges us to forbear, and therefore it is, I say, that we cannot. If there be no friendly arm to check us, or if we fail in a sudden effort to prostrate ourselves backward from the abyss, we plunge, and are destroyed.

Close cousin to Poe’s delicious terror is the nagging urge to help some deserving soul through Zion’s gates with a short, sharp nudge, over the edge. Watching a bubbly twentysomething snapping photos of her boyfriend, oblivious to the canyon’s breathtaking splendor, as he videotaped her (a scene that Baudrillard would have written, if it hadn’t happened), I found myself willing her to step back, back, just a silly millimeter more, toward the oblivion that beckoned, just outside the camera frame. Admittedly, the milk of human kindness was curdling in my veins, that day, soured by one too many braying, supersized sightseers. But tell me true: Who among us hasn’t wished one of the camcorder-clutching herd piling off that tour bus—stereotypes come to life, with their fanny packs and their overstuffed Dockers—would take one step too many while trying to locate Brianna in the viewfinder?

“What is it about us human beings—how we feel that, in any contest with nature, we’re fated to come out on top?,” writes Susan O’Neill, in her Amazon review of Michael P. Ghiglieri and Thomas M. Myers’s Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon, an enlightening compendium of fatally brainless hijinx, freak accidents, murders, and suicides, staged in a landscape of ineffable beauty—and terror. She attributes this hubris to, among other things, “a false sense of safety because, hey, we’re in a National Park, and surely a National Park can’t be any more dangerous than Disney World…” Ghiglieri and Myers’s gripping accounts of killer flashfloods and rockslides, of marathon runners found brain-dead in the broiling heat of the canyon’s desert floor, of a model capering inanely at a precipice’s rim while a photographer snaps away, only to capture the gut-clenching blur of something falling, read like Old Testament parables, newly revised for the age of reality TV. They’re cautionary tales for wired apes whose closest encounter with wild nature has consisted, until their pilgrimage to the Grand Canyon, of the concrete limbed-and-vinyl-leafed flora and Audio-Animatronic fauna of Disney’s Critter Country.

“Happy nowadays is the tourist, with earth’s wonders, new and old, spread invitingly open before him, and a host of able workers as his slaves making everything easy, padding plush about him, grading roads for him, boring tunnels, moving hills out of his way, […] spiritualizing travel for him with lightning and steam, abolishing space and time and almost everything else,” wrote Muir, in 1902. Worried, as generations of Rousseauvian discontents after him would worry, about the End of Nature, Muir lamented that the “tender, pulpy people…may now go almost everywhere in smooth comfort,” bringing with them, presumably, a Disneyfied vision of nature as the blue-screen backdrop for witless antics. I’m channeling the genocidal misanthropy of the Deep Ecologists, here, I realize, and the Luddism of Edward Abbey at his most Kaczynski-esque. Still, it’s hard to suppress the gag reflex triggered by our relentless anthropocentrism, our petulant insistence on reducing the irreducible to proportions manageable to the cortex of a self-important ape. How reassuring to think that here, at last, is a hole big enough to swallow our hubris, if we will only take the plunge.

Darwin Award Honorable Mention: An allegedly un-Photoshopped image of Ron L. Toms performing the allegedly unfaked “Grand Canyon Leap of Faith.” Photo: Dana R. Watson.

– © Mark Dery 2005