William Anthony Nericcio, Tex[t]-Mex: Seductive Hallucinations of the “Mexican” in America (University of Texas Press, 2006) .

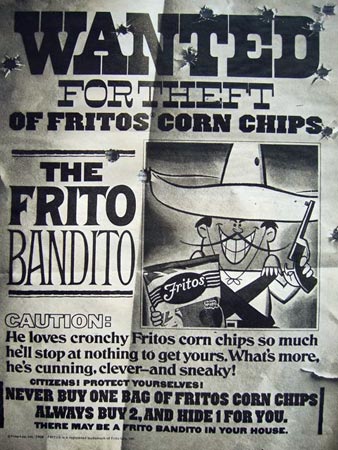

The irony of William Nericcio’s psychoanalysis (schizoanalysis?) of apparitions of The Mexican in the dream life of American culture is that Nericcio himself embodies—even as he appropriates and subverts—the stereotype of the Spanglish-speekeeng Trickster figure, tunneling under the heavily fortified borders between discursive zones. He’s the Speedy Gonzales of zoot-suit Derrideanism. Better yet, he’s the Mil Mascaras of critical theory, a masked semiotic wrestler pummeling multiple meanings out of the flotsam tossed up by our disposable culture.

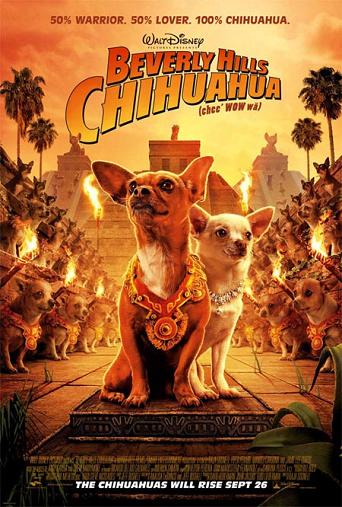

Drawing on post-colonial theory, Chicano/a studies, a deep knowledge of American history, a scary mastery of continental theory, and an undisguised delight in the retinal pleasures and greasy seductions of junk culture, Nericcio spins us around to face our image of The Mexican, and in so doing reveals it for the cultural mirror it really is, a funhouse reflection of Anglo America’s anxieties and fantasies about the Other. Ask not for whom the Taco Bell tolls, Lou Dobbs; it tolls for ustedes.

Text{e}-Mex crackles with a manic energy and an antic wit that are rare in academic writing, most of which tends toward soul-crushing ponderousness. Like the French philosophers who’ve clearly influenced his work, Nericcio tosses off oracular pronouncements without op. cits or apology and rejoices in wordplay. At the same time, his willingness to open the throttle on the passions that animate his arguments and take his rhetoric to telenovela heights of soap-operatic excess, pushing the envelope of his tropes and intertextual riffs into the ultra baroque, seems (to this gabacho, at least) profoundly Mexican. Here he is decrypting a “startling gringo artifact”—packaging for a toy called the Sparkling Clay Factory, featuring a hysterically Anglo boy and girl: “Check out these cute gringo kids from my private collection of ‘ethnic’ types (in particular, look closely at the boy on the right, who has been digitally processed so much that his ‘skin’ takes on the texture of a Pixar-born(e) computer-generated-image offspring of a CGI wet dream by the in vitro-cloned hybrid child of Mengele, Geppetto, and John Lasseter).” He deadpans, “I am still trying to figure out what planet the depicted organisms on this torn box cover come from.”

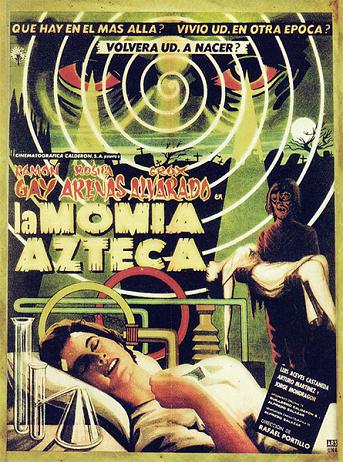

If you’re the sort of intellectual border-jumper who thinks Zizek would make the perfect guest host for Gustavo Arellano’s “!Ask a Mexican” newspaper column; if you fantasize about staging Foucault’s essay “The Masked Philosopher” as an off-broadway production starring lucha libre stars; if the next two items in your Netflix queue are Derrida and Wrestling Women versus the Aztec Mummy, Text{e}-Mex is your answered prayer.

But don’t say I didn’t warn you: Early on, Nericcio warns us that he’s an unreliable tour guide—(“ok, remember that your author is a recovering Catholic Tejano—idealism and the apocalypse lurk around every paragraph”)—and, like all the best intellects who run through the world like a Tijuana switchblade, he goes meta, stepping outside his own analytical paradigm to interrogate that, as well. “The germ of this book was a vendetta I had for an animated Mexican mouse by the name of Speedy Gonzales; but, in the end, I had to let the anger go,” he writes, in the book’s introductory chapter.” Tellingly, he quotes Baudrillard, the always ironic John the Baptist in our Desert of the Real: “Baudrillard…says: `It is always a false problem to want to restore the truth beneath the simulacrum.’ Look behind Speedy or beneath Freddy Lopez and one will not find Mexican-hating illustrators or Latino-loathing puppeteers…More often than not, one will find someone working sine dolo malo, “without fault, without an intent of evil…'” Text{e}-Mex is a cross between the red pill that gives Neo an ontological migraine in The Matrix and the worm at the bottom of the mezcal bottle. Nericcio shows you just how deep the bottle goes.