“Pipe Dreams: The Curious Case of Rene Magritte,” the latest in my ongoing series, “Self-Help for Surrealists,” is live at Thought Catalog.

Teaser:

The method Magritte used to solve his philosophical “problems,” as he called them, is a Surrealist’s idea of CSI, a combination of free association, semiotic codebreaking, and Hegelian dialectic. Bridging dream logic and what might be called visual reasoning, Magritte’s approach crosses Hegel with Lautréamont with automatic drawing, resolving thesis and antithesis in a startling, poetic synthesis of images.

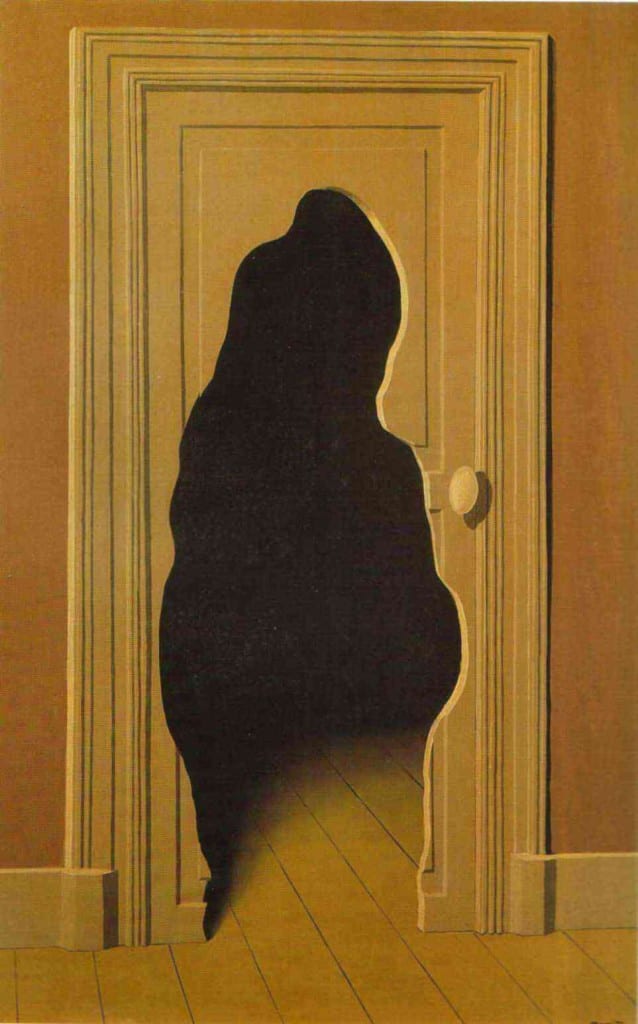

Case in point: The Problem of The Door. Solution:Unexpected Answer (1933), a door with an irregular shape cut out of it. Roughly the size of a hunched figure, the hole reveals a darkened room. We feel a prickling on the back of our necks, possibly because its undulating outline reminds us of the shrouded ghosts of gothic horror, or maybe because there’s just enough light falling across the threshold to pique our curiosity, tempting us to step into the unknown. It’s the door that makes the mystery, and Magritte’s door, with its peep-show view of a room full of shadow, is even more mysterious than a closed door. Which is spookier, the closed door to Room 237, the chamber of nightmares in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, or the same door ajar, key dangling jauntily, daring us to step inside for a little visit? In fact, Magritte’s door is more uncanny than either, since it combines the enigma of a closed door with the eeriness of one that opens into darkness, ominously beckoning.